Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

PRZEMYŚL

by Victor Yakovlev

Professor of the Nikolaev Engineering Academy

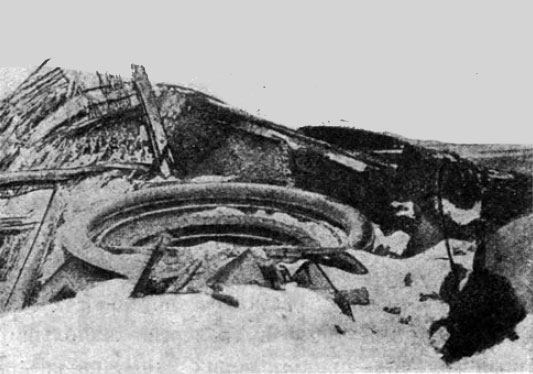

Destroyed armored howitzer installation, 1915

Foreword

The onset of spring in the current war period on our southwestern front was marked by the fall of the first-class Austrian fortress of Przemyśl. This event, of great moral and strategic significance, overshadowed all other military events, drawing worldwide attention and prompting extensive discussions on the pages of both domestic and foreign newspapers and journals, filled with reports from correspondents who managed to visit this new "Russian" fortress.

Unfortunately, almost all descriptions and correspondents' reports have been fragmented and fail to provide a comprehensive picture of the fortress's layout and the conditions of the struggle for it. Although they do offer interesting material from a technical and fortification standpoint—primarily through photographic images—they present it unsystematically and in language better suited for laymen rather than technicians and specialists in military engineering.

PRZEMYSL

Wanting to familiarize readers of the Engineering Journal as soon as possible, particularly with the fortification system of the fortress and the circumstances surrounding its siege and surrender, presented as a coherent whole, supported by recognized considerations and conclusions of a military-technical nature, we have compiled all available literary material on the subject and processed it into this outline.

Forced, for understandable reasons, to rely solely on data published up to the first half of April inclusively, we warn our readers in advance that much in our sketch may be incomplete or perhaps not entirely reliable to the degree desirable for specialists. Overall, our outline serves merely as a canvas, upon which patterns, if desired and possible, can later be woven by those of our military engineers who had the chance to participate in the siege and occupation of what, as the reader will rightly recognize, was indeed a powerful modern fortress.

The first construction works at Przemyśl date back to the 1850s, when the city, located on both banks of the River San, was encircled by a series of lunettes, situated 2 to 3 versts [1 verst = 1.067 km - AWW] from the bridges. These lunettes initially had a weak profile and were subsequently reconstructed and strengthened repeatedly. Generally speaking, these lunettes formed merely a weak double tête-de-pont along the banks of the San.

At that time, the Austrians considered the territory of Austria-Hungary adequately protected by the Carpathian range. They feared only that, in the event of war, our troops might bypass the Carpathians through the Kraków region and head directly toward Budapest and Vienna. Thus, their attention was entirely focused on Kraków, the only fortress at the time considered such in the full sense of the word. As for Galicia, the Austrians initially neglected reinforcing this area, not expecting a military confrontation with us at all.

Following the defeat in the war of 1866, Austria seriously began to consider protecting all its borders, and it was then decided to convert Przemyśl into a true fortress. However, development did not extend beyond improving the old fortifications, which eventually became the strong points of the central defensive perimeter. Only in the 1880s, when under German influence—Germany pointing to our allegedly aggressive intentions—the Austrians decided not to limit their defenses to the Carpathian line but to establish an additional defensive line ahead of the mountain range, composed of fortifications around Lemberg (Lviv), Mikolajów (Mykolaiv), and Halicz (Halych). It was then that they began expanding Przemyśl, constructing a new belt of forts and thereby transforming it into a large fortress-base for all of eastern Galicia, providing the Austrians with the confidence that "as long as Przemyśl stands, Galicia remains in Austrian hands."

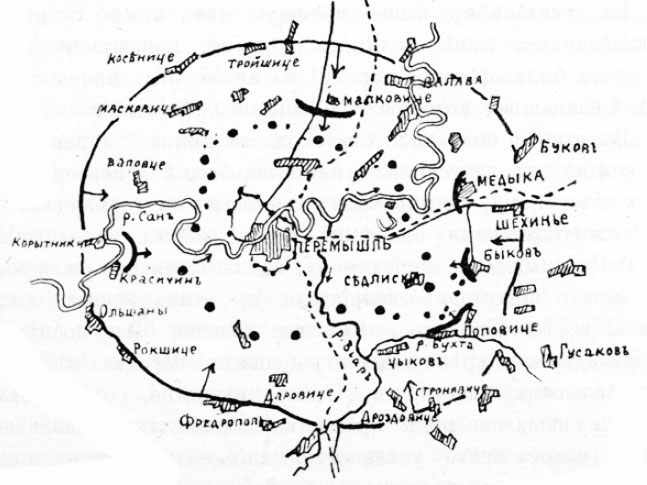

Among all the published plans depicting the overall arrangement of Przemyśl's fortress works, the diagram provided in the work of the late Professor Lieutenant-General N. A. Buynitsky, "Supplement to the book Engineering Defense of States" (published in 1909), deserves the highest trust. Being composed on the same scale (about 2 versts per decimeter) as the pre-war Austrian map of the surroundings of Przemyśl that was commercially available (published in 1891 by Artaria & Co. in Vienna), this diagram, when overlaid onto the mentioned map, provides a comprehensive view of the entire Przemyśl fortress. This served as our basis for using it in this form (see the map attached to the article) for our article.

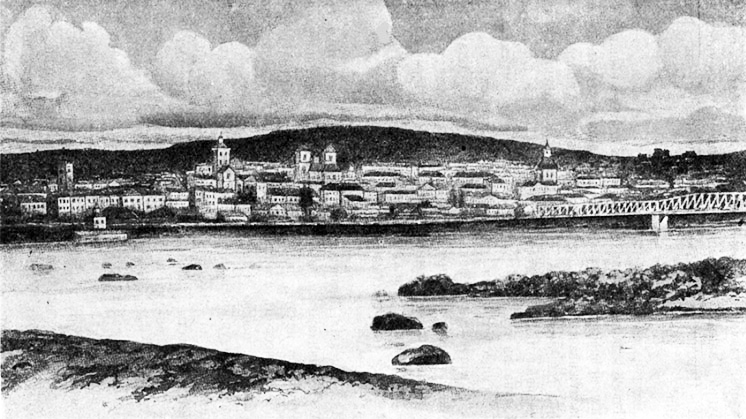

From the description provided in the above-mentioned work of N. A. Buynitsky, as well as from other descriptions published in the periodical press, it becomes clear that, at the start of the war, the fortification and topographical situation of Przemyśl was as follows: the core of the fortress is formed by the town itself, spreading along both banks of the river San, which divides it into two parts—the northern part, known specifically as the suburb Zasanie, and the southern part on the right bank of the river, situated partly on the plain and partly rising in terraces on high hills.

The position of the town itself—photographed and shown in Fig. 1—is extremely picturesque. It spreads out amphitheatrically upon a hill and is submerged in the greenery of gardens; church spires and ancient castle towers sharply stand out against a backdrop of mountains. Its narrow streets are adorned with numerous historic buildings dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries, while in the surrounding area are the ruins of castles built under King Casimir the Great in the 14th century.

Across the river San, within the town limits, three large bridges have been built: one railway bridge (see Figs. 2 and 3) and two wooden bridges, of which one is permanent—on the extension of the Lwów highway—and the other temporary.

Fig. 1. General view of the town of Przemyśl from the left bank of the River San.

Fig. 2. Railway bridge across the River San, destroyed by the Austrians after the fortress had been officially surrendered.

Fig. 3. Railway bridge across the River San—view from inside. Pedestrian traffic was restored by our sappers.

According to reports from certain correspondents, during the siege of the fortress, four additional bridges were built within its boundaries—apparently, not only across the River San but also across its tributary, the Wiar.

The core of the fortress was surrounded by a central enclosure of a modern type, consisting of five permanent strongholds and twenty weaker fortified positions, interconnected by curtain walls in the form of earthen ramparts and ditches, reinforced in places with barriers and nearly everywhere with wire entanglements. In general, the enclosure followed a closed curve extending from northwest to southeast, having a total length of approximately 15 versts. The average distance between the fortified points of this enclosure was about one verst.

The main defensive line was formed by a belt of forts, about 42 versts in circumference, containing, prior to the war, up to 42 fortifications. Among these were 19 permanent forts (9 large and 10 smaller ones); the remaining fortifications included either semi-permanent forts, weaker strong points, or permanent artillery batteries. Of these fortifications, 23 (including 10 forts) were situated on the right (eastern) bank of the San, while 19 fortifications, including 9 forts, were situated on the left (western) bank. The average distance between these fortifications was roughly one verst.

As for the distance separating the fort belt from the core fortress, it varied in different directions, mainly determined by terrain conditions and by the principal aim pursued by the Austrian engineers: ensuring protection of the railway bridge across the River San from artillery bombardment.

On the northern front, the terrain—less mountainous than in the west and south—did not restrict the Austrians, allowing them to place their forts nearly 6 versts away from the main crossing point, the railway bridge.

On the northwestern and western fronts, they had to occupy a natural defensive line along the villages of Orzechowce, Letownia, and Kuńkowce, which was preceded by a wide valley protected on its left flank by the bends of the River San. They had to settle for this position despite its proximity—just slightly over 4 versts—to the bridge. Apart from its defensive merits, the terrain further to the west rises considerably, and at 5 versts distance lies the strongly dominating height of Karezmarowa, the occupation of which would have pushed the defensive line excessively forward.

On the southwestern front, where the terrain posed no difficulties except for a few isolated heights requiring occupation, the fort belt was positioned roughly 5 versts from the bridge.

The southern, southeastern, and eastern fronts, enclosing the area between the River San and its tributary the Wiar, were intersected by the railway line that runs through Lwów (Lviv) and Brody into Russian territory, making these fronts most favorable for gradual attack. Considering this circumstance and local conditions—such as the valley of the Bukhta River (a tributary of the Wiar) passing through the village of Popowice—a valley which could not be left without proper artillery coverage, the Austrians advanced their fortifications here farther than elsewhere, almost 11 versts from the railway bridge. On the other hand, the presence of the commanding height of Medyka at 3½ versts to the east and the desire to cover themselves using the double bend of the San River caused the left flank of these fronts to be drawn backward, reducing the distance to the crossing to about 8 versts. Finally, the aforementioned necessity to control the Bukhta River valley—with its terraced slopes on the right bank—as well as the importance of this particular section of the fort belt, prompted Austrian engineers to organize here a separate group of six advanced forts, known as the "Sedliska group," named after the village of Sedliska located behind the main rear fort of the group, which was itself integrated into the general line of the fort belt.

All fortification works were interconnected by a network of fortress roads and railways, with the railways extending altogether up to approximately 100 versts. All fortress administrative centers, forts, and batteries were also serviced by telephone and telegraph networks.

According to the testimony of the visitors of the fortress, its general arrangement must be recognized as quite successful both tactically and in terms of fortification. It is true that many of the forts stand out conspicuously above the surrounding horizon and are clearly visible from a distance. However, this fact is explained by their construction during the era of brick fortifications (1880s), when the idea of camouflage had not yet been applied to fortress construction. Later, during reconstruction and concrete reinforcement in the 1890s, it became necessary to build these forts with high embankments. The fortifications constructed in later periods were apparently well camouflaged. From a tactical standpoint, the forts and other defensive structures were effectively adapted to the local terrain.

If we add to the above that the terrain, both within the fortress and along the line of the belt of forts and advanced positions, is quite rugged, partly wooded, and generally favorable for infantry and especially artillery (with many concealed and masked positions), then the strength of the fortress—in terms of the overall layout of its fortifications—becomes indisputable.

To obtain an idea of the construction and strength of individual fortifications from a purely fortification standpoint, we must partly rely on certain theoretical guidelines and partly on photographs taken after the surrender of the fortress and published by correspondents in various illustrated magazines, since other sources of information on this matter do not exist in the literature.

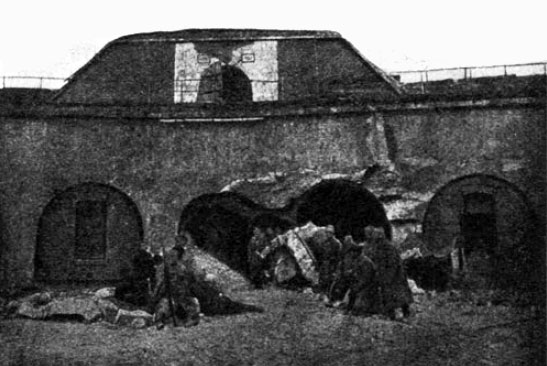

It is known that the construction of the central enclosure of the fortress dates from the period of the 1850s to the 1880s; hence, the main strongpoints of the enclosure are undoubtedly old—built from brickwork. This is fully confirmed by the correspondent's photograph shown in Fig. 4, published in issue No. 14 of the magazine "Iskry" ("Sparks")[*], depicting one of the enclosure's fortifications. In this photo, earthen traverses, a brick retaining wall, and what appears to be a forward ditch filled with water are clearly visible. In the distance, a winding section of the intermediate line between strongpoints is discernible. On the right, one can make out a bend in the River San.

*All the photographs mentioned are borrowed from the following magazines: "Letopis voiny", "Ogoniok", "Iskry", "Solntse", "Dobrovolets", "Zarya", "Vsemirnaya Panorama", "Niva", and "Razvedchik".

Fig. 4. One of the secondary strongpoints of the enclosure.

Whether the brick constructions of the enclosure were reinforced with concrete during the 1890s is unknown; one can only doubt this, since the enclosure was of secondary importance, and it is unlikely that the Austrians would have paid as much attention to it as they did to the belt of forts. Possibly, only ammunition magazines may have been reinforced with concrete. In general, it is more plausible to assume that any upgrades carried out on the enclosure were predominantly earthworks or related to setting up artificial obstacles.

One can assume that structures of a similar nature to the strongpoints of the enclosure are also found in certain fortifications placed slightly forward from the latter—for instance, the structure, apparently a battery, situated southwest of the town near the village of Krugel, as well as other similar installations that form a kind of second defensive line behind the belt of forts. Apparently, Fig. 5 shows a photograph belonging either to one of these fortifications or possibly to one of the enclosure's strongpoints.

Fig. 5. One of the secondary fortifications of older construction.

As for the fortification belt—as previously mentioned—the construction works began there in the 1880s. All the fortifications built during that period were undoubtedly brick structures; subsequently, many of these were reinforced with concrete in the 1890s. Additionally, several forts appear to have been erected within the 13 years preceding the war. Finally, according to some correspondents, six semi-permanent fortifications were constructed very recently, apparently completed only just before the start of military operations. Thus, on the fortress belt, there should be structures of various types and constructions, numbering up to 50.

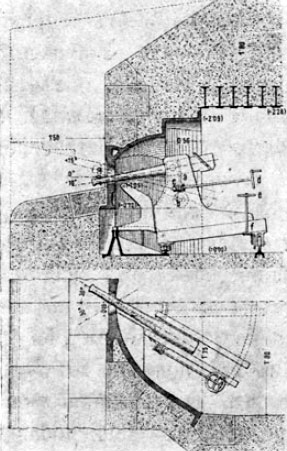

If we turn to theoretical examples of permanent fortifications recommended by Austrian engineers in their textbooks and handbooks, we can find indications that in the 1890s (see the manual then adopted in Austria by Lieutenant Colonel Leitner, who held the high post of Inspector General of Fortresses and Engineering Troops in the early 1900s—Die Beständige Befestigung und der Festungskrieg, published in 1894), Austrians considered the following types of fortifications suitable for the fortress belt:

1. Gürtel-Hauptwerk or Panzerfort—i.e., armored fort-battery;

2. Nahkampf-Stützpunkt or Lagerfort—a close-combat strongpoint or fort-redoubt, sometimes equipped with armored turrets for anti-assault artillery, sometimes left without;

3. Fernkampf-Batterien—permanent batteries for long-range artillery, either open or armored;

4. Gürtel-Zwischenwerke—intermediate forts;

5. Werke—weaker types, usually semi-permanent fortifications.

The favored type in the 1890s was apparently the fort-redoubt equipped with armored installations. In general, this was a permanent fort featuring a gorge barracks—brick-built but reinforced with concrete—with similar shelters beneath the terreplein façade in the middle and at salient angles. Above these shelters stood armored cupolas housing rapid-fire 7.5-cm field guns. Ditches were protected by separate brick walls, partly replaced by iron grilles, and brick-built but concrete-reinforced caponiers and half-caponiers, though in some cases ditches were defended from concrete counterscarp coffers connected by concrete counterscarp galleries. Intermediate half-caponiers (Traditor-batterien) were often constructed at the sides of the gorge barracks in such forts.

Judging by the correspondents' photographs presented below, most of the Przemyśl forts were precisely of this type. Thus, Fig. 6 depicts the gorge of one of the main forts. The photograph shows a brick-built barracks of the older type, reinforced with concrete; this is largely intact, with only the adjacent central gorge caponier torn away and damage to the right extremity of the barracks itself. Above the barracks, casemated traverses with concrete entrances leading into shelters or ammunition magazines are visible—these represent the remains of an older open artillery position situated above the residential barracks. In newer fort designs, such open batteries were typically replaced by armored cupolas with 12-cm or 15-cm howitzers positioned atop the usually two-story barracks.

Fig. 6. Gorge barracks of one of the main forts, with casemated traverses above it.

Fig.7. The central part of the barrack block of one of the forts.

Fig. 7 provides a closer view of the central portion of a similar gorge barracks in another fort—according to the caption in the journal Ogoniok—Fort Hurko, located on the eastern front of the fortress. In this photograph, the brick construction around the windows, as well as the concrete reinforcement of the remaining part of the barracks, can be seen clearly. A concrete entrance to a shelter or ammunition store beneath a traverse located above the barracks is also visible. Finally, one can observe how the gorge caponier was torn off due to an explosion.

A similar type of destruction is shown in Fig. 8, where the caponier detached from the gorge barracks is of metal construction; near it, to the side, lies an iron chevaux-de-frise wrapped in barbed wire—one of the various types of obstacles employed by the Austrians on their forts.

Fig. 8. A metal caponier, detached by explosion from the central portion of the gorge barracks.

Fig. 9. Destroyed section of one of the main forts.

In Fig. 9, another photograph depicts the gorge section of another fort. This photograph indicates a gorge structure similar to those described above. The explosion has destroyed the lower brick wall as well as, apparently, the concrete gateway (on the right) leading inside the fort, and the concrete entrance to the traverse shelter above.

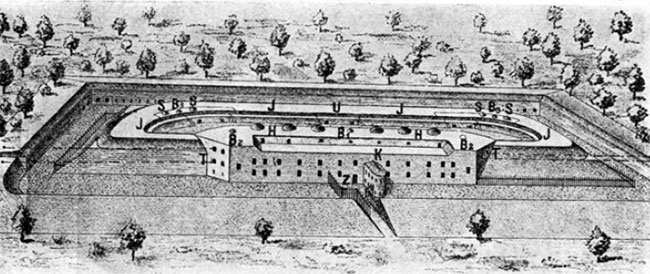

Fig. 10. The latest theoretical model of an Austrian fort in axonometric projection.

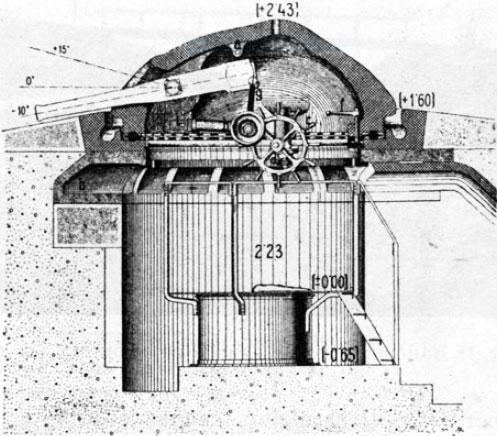

Unfortunately, no photographs providing a complete view to judge the construction of an entire fort—especially one of the newer type—were published in any of the journals. However, from photographs of individual elements of various forts, some of which are shown below, one may conclude that in Przemyśl there indeed existed forts closely approximating the theoretical models encountered in recent Austrian textbooks.

Thus, in the semi-official publication by Lieutenant Colonel of the Engineering Staff Moritz Brunner, "Die Beständige Befestigung," 1909, as well as in the military-technical reference book by Lieutenant Tsagayevsky, published in 1913, an axonometric projection of the newest model of an Austrian fort is shown (Fig. 10).

In this figure, the following designations are used:

• K – gorge barracks with a central caponier and intermediate half-caponiers T at the ends.

• H – armored rotating cupolas with 15 cm howitzers.

• S – armored rotating cupolas with 7.5 cm rapid-fire guns.

• B1, B2, B3 – armored observation posts.

• J – infantry firing positions.

• U – shelter beneath the parapet, connected by a postern to the gorge barracks and counterscarp gallery of the front face.

• Z – iron tambour protecting the entrance to the barracks.

The presented fort model, being purely theoretical, hardly embodies any of the Przemyśl forts entirely. It is quite possible, of course, that several forts within the fortress resembled the type depicted here, but with certain deviations from the theoretical model (*).

*In the issue of the journal "L'Illustration," dated April 17 (new style), there is a drawing of a fort analogous to the one shown in Fig. 10, indicating that the fort "Wolestracice" in the northeastern sector had such a layout, and four other forts were of similar construction: two on the eastern sector, one on the southeastern, and one on the northwestern sector.

For example, the photograph in Fig. 11 shows a destroyed gorge barracks of one of the forts, evidently of a more modern type, as the barracks is concrete and two-storied—features already matching what we see in the theoretical example in Fig. 10. It is difficult from the photograph to determine whether such a barracks had armored cupolas with howitzers atop its forward part, but there is no doubt that such armored howitzers were present in the fortress. This is confirmed by an official report dated April 4, stating that we captured within the fortress "48 armored turrets for artillery ranging in caliber from field guns up to and including 6-inch guns." Consequently, among these turrets, some were equipped with howitzers. It should be added, however, that these turrets may not have been solely on forts but also on intermediate armored batteries, to which the Austrians resorted in recent years.

Fig. 11. A two-story gorge barracks in one of the forts, destroyed by explosions.

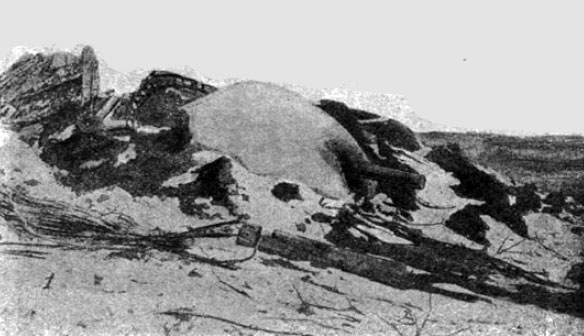

Fig. 12 presumably depicts one of these armored howitzer batteries, damaged by the Austrians upon surrendering the fortress.

Fig. 12. Destroyed armored battery.

Fig. 13. Armored mounting of a 7.5 cm gun in the casemate of an intermediate half-caponier.

However, with equal certainty, it can be assumed that the photograph relates to destroyed armored turrets with rapid-fire guns, since the guns themselves are not visible, and the construction of turrets for howitzers and for guns is very similar.

The presence of intermediate half-caponier positions (Traditor-batterien) in some of the Przemyśl forts is again confirmed by the above-mentioned official report, according to which "48 installations for flanking the intervals" were captured by us in the fortress. Fig. 13 shows such an installation for a 7.5 cm rapid-fire gun, taken from an Austrian fortification textbook: the gun is mounted on a special carriage, rotating on rollers around a fixed axis, with its front part placed into a semicircular niche in the front wall of the casemate. This niche is armored on three sides and on top. The roof of the casemate consists of I-beams and six feet of concrete.

The individual casemates are apparently arranged in a stepped manner relative to one another.

Fig. 14. A destroyed concrete shelter with armored turrets for rapid-fire guns.

As for the armored mounts for field-caliber guns, similar to those shown at the salient angles of the theoretical fort model in Fig. 10, the existence of such installations in some Przemyśl forts is suggested by the photograph in Fig. 14, which shows the destroyed front face of one of the main forts. In this photo, three armored turrets can be distinguished, crowning a concrete shelter beneath the parapet. The furthest turret appears to have suffered little damage, as the dome is visible with the gun barrel protruding from it; on the other two turrets, the domes have become detached from the rest of the structure, and the guns are no longer visible.

On the sides of the concrete shelter, rifle positions can be seen near the earthen part of the parapet, with steps leading up to them and with makeshift field-style canopies (shelters) constructed above.

Fig. 15 shows a similar section of parapet with armored turrets for field guns in another fort. In the photograph, one of the surviving turrets is visible, with a 7.5 cm field gun protruding from it; everything around the turret is destroyed.

Fig. 15. Section of the parapet of one of the forts with a surviving armored turret for a rapid-fire gun.

Fig. 16. Armored turret with a 7.5 cm rapid-fire gun made by the Škoda Works in Pilsen, model 1894.

Fig. 16 presents a photograph of an armored turret with a 7.5 cm field gun, still intact on Fort No. 5. (*) On the front armor, one can make out an inscription indicating that the turret was manufactured at the Škoda Works in Pilsen in 1894. The detailed internal structure of such a turret is well known from Austrian textbooks and is shown in Fig. 17; rotation, using a handwheel and a circular toothed track (d), is carried out on ball bearings. The armor thickness at the top of the dome is about 25 cm.

*"Iskry" Magazine, No. 13.

Fig. 17. Armored turret with a 7.5 cm rapid-fire gun by the Škoda Works, shown in cross-section.

Whether Przemyśl’s forts were equipped not only with armored mounts for anti-assault guns but also with armored observation posts, as shown in the theoretical model in Fig. 10, is difficult to say, since no traces of them can be found in the available photographs.

To conclude the description of the actual fort constructions in Przemyśl, it remains to speak of the ditch-flanking structures and obstacles.

As for the structures flanking the ditches, considering that most forts were begun in the 1880s, it is reasonable to assume the presence in some of them of older brick caponiers and half-caponiers, which were reinforced with concrete in the 1890s. The existence of such structures is confirmed by the photographs in Figs. 18 and 19, where one of these structures is clearly visible. Apparently, the photos depict the end or side ditches of a fort—in any case, sections where the construction was safe from direct enemy fire from the field.

Fig. 18. Caponier in the ditch of one of the forts (viewed from one side).

Fig. 19. Caponier in the ditch of the same fort (viewed from the other side).

It is, however, beyond doubt that the more important forts, which were reconstructed in the 1890s or newly built from that time onward, were equipped with coffres—counter-scarp flanking structures—as their flanking installations. From the semi-official manual by Lieutenant Colonel Leitner, published in 1894, it it’s evident, that coffres in Austrian forts were structures very similar to traditional caponiers, with the addition of rifle galleries alongside gun casemates.

The construction of such a section of a coffre is shown in cross-section in Fig. 20. The rifle gallery is about 5 feet wide; the front wall features stepped embrasures with internal steel shields. At the top of the wall runs a ventilation opening (air vent), above which is a metal protective mesh designed to prevent damage to the vents, embrasures, and loopholes by explosive projectiles rolled up by the enemy during a close-range attack. At the base of the front wall is a wire fence mounted on metal stakes.

Fig. 20. Cross-section of a coffer with an adjoining rifle gallery.

In those sections of the coffres where artillery installations were planned, the internal layout was similar to that in intermediate half-caponiers (see Fig. 13)—a casemate of appropriate dimensions was built, with the semicircular front wall and the ceiling above the gun's position armored. The presence of such installations in some of the Przemyśl forts can be inferred from our official report, which mentions among the captured trophies “20 armored installations for ditch flanking.”

Judging by the descriptions and diagrams presented in the above-mentioned manual by Lieutenant Colonel Leitner, entire sections of counter-scarp galleries—equipped with embrasures and loopholes—were often attached to coffres in Austrian forts of the 1890s. In Figs. 21 and 22, which show photographs of separate sections of destroyed Przemyśl forts, fragments are visible that were apparently parts of such counter-scarp galleries, blown upward by the force of explosions.

Fig. 21 shows a photo from the interior of a fort near the parapet: on the right side in the background, shelters are visible; in the foreground are fragments of concrete and separate parts of cornices from concrete structures, into which iron posts and rail brackets were embedded. In the background on the left, a rounded portion of a defensive concrete structure can be seen, which appears to be, or is assumed to be, part of a counter-scarp gallery or the front wall of a flanking structure.

Fig. 21. Interior part of the destroyed parapet section of one of the forts.

Fig. 22 shows a portion of a concrete counter-scarp gallery—apparently blown from the ground and thrown up onto the escarp—with seven embrasures. For those who have witnessed the demolition of concrete structures, the effect of such an explosion is well understood: according to correspondents who visited the destroyed forts, individual concrete blocks and sections of structures were thrown 6 to 8 sazhen (12–16 meters) from their original positions.

Fig. 22. Destroyed and explosion-thrown section of a counter-scarp gallery equipped for artillery defense of the ditch.

Fig. 23. Wire entanglement on metal stakes, man-height.

As for the use of artificial obstacles on the Przemyśl fortifications and forts, all available photographs confirm that the most common were wire entanglements. These ranged from the simplest—made of wooden stakes and plain wire, used in less critical areas—to full-scale fences made of man-height pointed metal rods wrapped in barbed wire, as seen in Fig. 23, which shows this type of barrier in front of a section of the main defensive line.

Additionally, tin cans from rations were hung on the wire, whose clattering was meant to alert defenders of an approaching enemy—this method was already used in the Russo-Japanese War.

Among other obstacles seen in photographs were metal and wooden chevaux-de-frise, wrapped in wire. Regarding the use of iron grilles in the ditches of forts, and in older types of fortifications, separate brick walls, this can only be assumed, as no photographs exist to confirm it. According to some correspondents, fougasses (improvised explosive charges) were also widely used among the artificial obstacles.

Figs. 24 and 25 show photographs of the entrance to one of the forts of old but solid construction. In Fig. 24, the gorge rampart with a ditch and wire entanglements on the glacis is visible; a wooden footbridge is thrown across the ditch, blocked by a chevaux-de-frise moved to the side. In Fig. 25, the gate is visible, made of stone with support pillars and metal lattice doors.

Fig. 24. Gorge section of one of the forts with its entrance (view from the outside).

Fig. 25. Gorge section of one of the forts with its entrance (view from the inside).

Fig. 26. Destroyed armored howitzer installation.

Regarding the construction of permanent batteries that were used in Przemyśl, there are no specific details in the various published reports. However, based on some indirect indications and partly from photographs, it can be assumed that both armored and open batteries were present. Armored batteries, judging by Austrian manuals, were similar to those of the Germans—that is, massive concrete structures crowned with armored cupolas housing 15 cm howitzers. On the enemy-facing side, the structure was covered with earth and surrounded by a ditch with wire entanglements, which received frontal defense from a rifle position built into the outer edge of the earthen covering. The approaches to the gorge were flanked by fire from a gorge caponier attached to the concrete mass.

In Fig. 26, the remnants of a destroyed howitzer installation are visible—apparently once housed under an armored cupola.

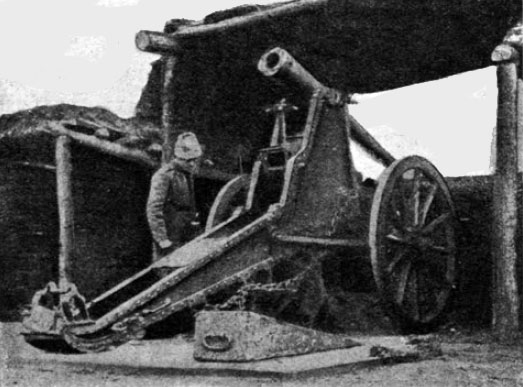

Fig. 27. Field gun installation on an open permanent battery.

Open batteries consisted of a series of gun emplacements separated by casemated traverses, with an earthen parapet in front of which a ditch with wire entanglements was dug. These batteries were armed with both guns and howitzers. Fig. 27 shows a gun installation on an open permanent battery. Judging by the photograph, the original installation was a pedestal mount for all-around fire, but afterward—likely after it was damaged—a gun was mounted on a wheeled carriage instead.

In addition to permanent batteries, during the mobilization period and the subsequent lifting of the siege, a significant number of temporary batteries were undoubtedly built behind the fort belt. The simplest of these batteries, as evidenced by the photograph in Fig. 28 (taken from the British Illustrated London News), consisted of gun platforms between earthen embankments—traverses—under which were constructed small dugouts made from corrugated iron, shaped in an arch and supported by wooden posts forming the frame of the side walls of the shelter. A thin layer of earth (apparently about 1½–2 feet) was piled over the iron. Up to three dugouts were located under each traverse. The gun crews were apparently housed in tents pitched behind the traverses, or perhaps partly in the same type of dugout as the ammunition shelters.

Fig. 28. Intermediate battery of temporary character.

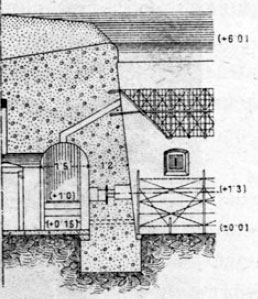

Another type of structure that could be found on the outer perimeter of the fortress, as well as between it and the enclosure, was the semi-permanent fortification, playing the role of intermediate forts and secondary strongpoints. According to the latest manual (published in 1909) by Lieutenant Colonel Brunner, these kinds of fortifications—like those in Germany—consisted of a concrete barracks, covered with earth on the enemy-facing side and additionally fronted by an earthen parapet and ditch with obstacles. These obstacles were either left undefended or had only frontal defensive arrangements.

Fig. 29 shows a photograph of such a fortification on the fort belt of Przemyśl. In the foreground, a very simple concrete barracks-shelter is visible, with entrances protected by small straight passageways; in the background, a rifle position with pole-and-cloth covers is seen. Judging by the photo, the walls and vaults of such barracks were unlikely to be more than 3 feet thick.

Fig. 29. Interior view of one of the semi-permanent fortifications.

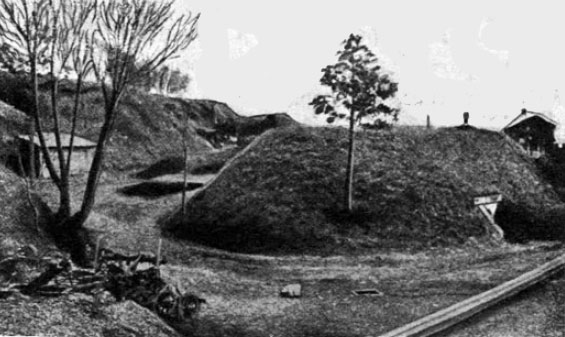

Fig. 30. One of the powder magazines.

Fig. 30 shows a photograph of one of the powder magazines in Przemyśl. These magazines, apparently made of concrete and covered with a significant layer of earth, could have been located both within the enclosure and in the area between it and the fort belt.

To complete the description of all the fortress fortifications of Przemyśl and to draw the corresponding conclusions, it remains to touch upon some details of a technical nature and the works carried out during the mobilization period.

For an engineer dealing with fortress matters from a technical standpoint, it is, of course, extremely interesting to determine the structural strength of a construction in terms of its resistance to siege artillery. For this, it is necessary to know the construction’s design, its dimensions, and the caliber of the artillery used to bombard it.

Regarding the Przemyśl fortress structures, the first question can be clarified here with some degree of certainty; as for the question of the siege calibers used to bombard the works, for understandable reasons, this cannot presently be discussed in print, and therefore we must limit ourselves to purely theoretical considerations, without referring to this specific case.

From the descriptions given above concerning the general design of those structures that may have existed in Przemyśl, it is evident that the primary materials used for their construction—besides, of course, earth—were brick, concrete, and armor plate. Some correspondents who visited Przemyśl gained the impression that Austrian engineers also used reinforced concrete for the fortress structures, but this appears to be a misunderstanding. In none of the latest Austrian manuals or reference works is the use of reinforced concrete coverings in fortress structures mentioned; however, it is true that such applications may not have been publicly disclosed but might have occurred in practice.

However, correspondents describing the forts they saw mention coverings composed of iron, then concrete, and then earth, and refer to such coverings as "reinforced concrete," whereas any engineer knows that these are not reinforced concrete but ordinary flat coverings made from iron beams with a layer of concrete. Such coverings were recommended by Austrian manuals even for buildings like barracks; for less important buildings, it was recommended to lay the beams with gaps, placing corrugated iron on top and then adding concrete over it.

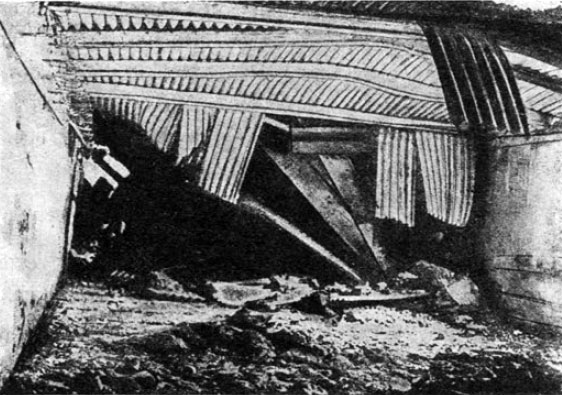

The presence of such types of coverings, at least in some of the Przemyśl fortifications, is confirmed by the photograph in Fig. 31, which shows the interior of one of the casemates—likely destroyed by explosions—consisting, as can be seen, of concrete walls and a ceiling made from I-beams, corrugated iron, and a layer of concrete. According to theoretical diagrams, the thickness of this concrete layer ranged from 1.5 to 2 meters; whether this thickness was actually followed in practice is unknown, but judging by the thicknesses of arched coverings, it can be assumed that even in flat coverings, the concrete thickness hardly exceeded 4 feet.

Fig. 31. Interior of one of the destroyed casemates.

Our doubts regarding the use of reinforced concrete by the Austrians in Przemyśl are also based on the consideration that almost all of the main fortifications of the fortress were built in the late 1890s and early 1900s—that is, at a time when the practical application of reinforced concrete in fortress construction was not even being considered. Consequently, if reinforced concrete was used at all in Przemyśl for casemate coverings, it was only partially. In general, it should be assumed that there were three types of covering: unreinforced brick, reinforced brick (typically with concrete), and concrete—either flat or vaulted. The thickness of the vaulted concrete coverings can be estimated approximately from the photographs provided earlier: it appears to be no more than 4½ to 5 feet.

Regarding the armored turrets found in Przemyśl, judging by the manufacturer’s mark—for example, on the turret shown in Fig. 16—it can be said that they were old models from the 1890s, manufactured by the Škoda Works, with an armor thickness of about 25 cm.

The data provided, combined with what is known theoretically about the resistance of such constructions to modern high-explosive shells, allow us to conclude that most casemates in the Przemyśl forts could withstand only bombs no larger than 6-inch caliber. The use of more powerful shells, especially combined with intense fire, would undoubtedly have destroyed many of the coverings; armored installations could also have suffered damage.

To form a final understanding of the technical strength of the fortress, a few more words must be said about the works carried out during the mobilization period (August) and during the lifting of the siege (almost all of October).

Whether any concrete work was carried out in the fortress during these periods is not precisely known; however, one correspondent reported that a cement plant existed in the city, from which cement mortar was delivered to the fort belt for various construction works.

The main efforts during the mobilization and siege-breaking periods were focused on the improvement of the forts, strengthening of the intervals between them, clearing of the terrain in front, and occupation of forward positions.

On the forts, judging by photographs, great attention was paid to improving open rifle positions; on the parapets, field-type shelters with loopholes and canopies were constructed from stakes, poles, rows of branches or rods, then boards, and a thin layer of earth to provide cover from shrapnel bullets and small shell fragments. Such field-type shelters were evidently built on all fortifications, as clearly shown in the previous photographs presented in Figs. 14, 21, and 29.

Similar types of canopies, as seen in Fig. 32, were also built above gun and machine gun emplacements.

Fig. 32. A gun under a shelter.

On some fortifications, additionally, enclosed dugouts protected on all sides were constructed, similar to the one shown in Fig. 33.

Fig. 33. Dugout for personnel at a rifle position.

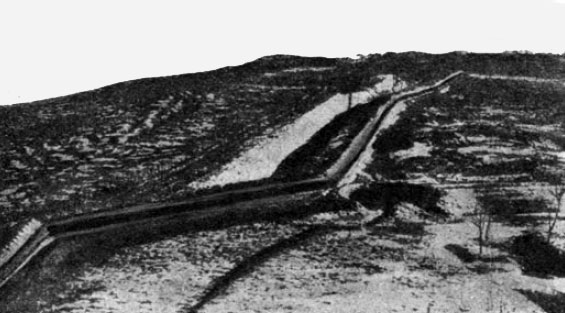

Work between the forts and in the area between the fort belt and the inner enclosure appears to have involved the construction of certain strongpoints, rifle trenches, and the installation of wire entanglements. In Fig. 34, a photograph is shown of a trench built at the side of one of the forts. The trench appears to have the profile of a rifle trench but with a glacis-like parapet transitioning into a ditch; this ditch, judging by the photograph, is filled with snow or water, and in front of it a multi-row wire entanglement has been installed with stakes.

Fig. 34. One of the trenches in the interval between the forts.

According to numerous correspondents, all the intervals between the forts were dug up with trenches and communication passages, and in front of them, segments of wire entanglement lines were stretched, with wooden stakes alternating with metal rods sharpened at the top. The network was 3–4 sazhens (about 6–8 meters) wide and came under both frontal and flanking fire—either from the trenches or from the forts themselves.

According to the same correspondents, the entire area in front of the fort belt had been prepared for the impending fortress battle: in many places, entire groves were cut down, villages were burned, and in some sectors, advanced positions were prepared, where after the siege a large number of rifle trenches reinforced with wire entanglements and abatis were also found.

By the time of the fortress’s surrender, its garrison numbered approximately 120,000 men. If the casualty figure of 40,000 men during the siege—reported in the literature—is accurate, then the total strength of the garrison since the beginning of the first blockade would have been about 160,000 men. Assuming that after the Galician battle around 100,000 men—remnants of the defeated armies of Auffenberg and Dankl—had taken refuge in the fortress, then the original fortress garrison would have been about 60,000, which must be considered normal by theoretical standards. Although one report from the Austrian High Command (see the telegram from the special correspondent of Birzhevye Vedomosti from Copenhagen dated March 31) states that “according to the old defense plan, the fortress was to have a garrison of 85,000 men,” this figure for the initial garrison size is not confirmed by any of the correspondents who spoke with prisoners and civilians from the surrendered fortress. On the contrary, according to the latter, the fortress’s food supplies had been calculated for a garrison of only 40,000 men. Therefore, in general, the figure of approximately 60,000 as the initial garrison size can be considered accurate, including, in addition to infantry and cavalry, about 5,000 artillerymen and 2 battalions of engineering troops.

The fortress’s artillery armament, according to some data, consisted of no fewer than 1,200 guns at the beginning of the siege; by the time of the surrender, some sources suggest that the total number of fortress and field guns reached up to 2,000. The guns were of the most varied calibers, ranging from 7.5 cm field guns to four 30.5 cm (12-inch) mortars, which were apparently brought into the fortress during the October relief operation.

Judging by official reports and data given in correspondents’ letters, the fortress had weapons of all kinds and stamps—from 1861, 1880, and more recent years. There were also old 9 cm and 15 cm guns, new 10.5 cm, 12 cm, 15 cm, and 18 cm howitzers, and finally, 24 cm mortars—eight of which were found at the time of surrender.

As for technical troops stationed in the fortress, they included: 2 sapper battalions, 1 or 2 aviation companies with at least 12 airplanes, 1 balloon company with several balloons, a radio station, and carrier pigeon service.

In addition, Przemyśl housed various supply depots: quartermaster, engineering, artillery, medical, and others; a huge food storehouse, steam mills, military bakeries, and a canning factory.

Among the artillery facilities in the fortress were: an artillery depot with stored guns, carriages, mounts, ammunition boxes, and several hundred old-model rifles; an artillery laboratory, powder magazines, and a dynamite depot.

Among engineering supplies were depots of portable field railways and all kinds of technical means, such as searchlights, signal rockets, land mines, and more.

By rough estimate, the fortress cost the Austrians no less than 100 million rubles.

From the above description of the fortress's structure and the means at its disposal, a completely definite conclusion can be drawn: this was indeed a first-class modern fortress. The Germans and Austrians attached great importance to it and considered it "the best fortress in Europe, whose siege by the Russians might last a year or more." It is said that the late Archduke Ferdinand once remarked: "My Przemyśl securely blocks the access to the Carpathian passes." Wilhelm also held a high opinion of Przemyśl’s strength: "I have seen your Przemyśl and am very pleased with it," he told the Archduke during the 1912 maneuvers in Breslau.

The local population of Galicia believed in Przemyśl so firmly that they held the unshakable conviction: "He who holds Przemyśl holds all of Galicia; and as long as Przemyśl is not taken, the Russians only temporarily control Galicia."

Strategically, Przemyśl as a fortress was extremely important to the Austrians, as it protected the crossings over the San River. At the same time, it was a major railway hub leading to Vienna and Budapest. Situated only 60 versts (approximately 64 kilometers) from the Russian border, this fortress was intended to block our army from pursuing a favorable operational line in an offensive either from the Warsaw Military District toward the Carpathians and into Hungary, or from the Kiev Military District westward toward Kraków.

Moreover, relying on Przemyśl and the temporary fortified positions adjacent to it on the San River—Radymno and Jarosław—the Austrian army, operating on both banks of the San, could advance within the area between the San, the Vistula, and the Western Bug Rivers, while simultaneously defending access to the Hungarian capital, Budapest. In the event of unsuccessful offensive operations, Przemyśl was intended to secure and cover the retreat through the Eastern Beskids, in the zone of western Galicia.

Before we now move on to recounting the circumstances that accompanied the siege and defense of Przemyśl, let us touch on the events preceding the struggle for the fortress and the role the fortress played during those events.

When the war began, the Przemyśl region, as is known, served as the launching point for the invasion of our territory by the armies of Dankl and Auffenberg (the Kraśnik and Tomaszów battles)—on one hand—and the armies of Lwów and Archduke Joseph Friedrich—on the other. The first group of armies, totaling about 600,000 men, deployed along the front from Zawichost to Tomaszów (see Fig. 35*) to advance against our Lublin–Chełm front. The second group of armies, numbering about 200,000, protected the right flank of the first and was deployed to the east of Przemyśl.

Fig. 35. Diagram of the positioning of the Austrian armies by the end of the Galician battle (August 30, 1914).

*In Fig. 35, the number of the northern armies is mistakenly shown as 800,000.

On August 12, the famous Galician Battle began, reaching its climax by August 21, that is, by the time General Ruzsky’s army took the Lviv positions. On August 22, the continued successes of Generals Ruzsky’s and Brusilov’s armies led to our general offensive and made it possible to break the connection between the Kraśnik and Tomaszów armies. By August 24, the Austrians in the Lublin and Chełm directions were already in full retreat, and only in the area of Rava-Ruska were fierce battles still ongoing. Finally, by August 30, Austrian resistance was completely broken and turned into a disorderly withdrawal.

The first two armies retreated to crossings over the San River between Sandomierz and Jarosław, heading toward Kraków; the second group retreated to the Jarosław–Przemyśl line, covering their withdrawal with a strong rearguard that occupied a fortified position at Horodok.

The defeat we dealt to the Austrians in the Galician battle was so great, and the pursuit of the defeated enemy so swift, that already by September 3 the troops of General Ruzsky’s army had taken the Horodok position and, advancing without pause, reached Mostyska, coming within 28 versts (approximately 30 kilometers) of Przemyśl from the east—that is, within a day’s march.

Operations to the north and southeast of Przemyśl developed just as successfully for us: by September 5, our troops had taken the bridgehead fortifications on the San River at Sieniawa, and four days later the Russian flag was already flying over the fortifications of Jarosław—only 35 versts (roughly 37 kilometers) from Przemyśl—which protected the railway junction connecting Przemyśl with Kraków.

Around the same time, in the southeast, troops from General Brusilov’s army occupied the fortified position at Sambor, whose bridgehead defenses guarded the Dniester River crossing and were just 20 versts (about 21 kilometers) from Khyriv, a key railway junction on the line from Przemyśl to Hungary.

By September 10, in the north, our forces were already at Radymno, just 11 versts (about 12 kilometers) from Przemyśl, and in the east, as early as September 7, at Medyka—only 2 versts (around 2 kilometers) from the forts. Combat with the Przemyśl garrison began at this point, and the fortress artillery opened fire. Thus, by September 7, the fortress was surrounded on three sides, and the blockade began.

In the overall course of these events, the role that the fortress had to play is clearly seen. Initially, when the Austrians undertook their offensive into our territory, Przemyśl covered the concentration of their armies and served as a base for them. Then, during the two-and-a-half-week Galician Battle, the fortress reliably ensured the supply of ammunition and food to the armies fighting to its north and east; it served as a rear staging post: the wounded were brought here, and the remnants of defeated armies found shelter here—which, as we shall see below, became the primary cause of the fortress’s swift fall.

With the conclusion of the Galician battle and the retreat of the Austrian armies to Kraków and the Carpathians, the role of Przemyśl changed: the fortress ceased to serve the Austrians as an operational base, as a support for the flank or center of their deployed forces, but instead became a significant obstacle to our further operations. By cutting off the best railway lines, the fortress diverted our transport to secondary and roundabout routes, restricted the freedom of our movements, and compelled us—if not to besiege it—then to blockade it, thereby requiring a certain number of troops that could have been used in further offensive operations.

In general, even though the fortress no longer fulfilled its main role, assigned to it during peacetime—namely, to delay our advance toward the Carpathians, as it turned out to be possible to bypass it—it nevertheless drew our attention and attracted part of our forces.

After the preceding brief summary of the events leading up to the struggle for the fortress, we now turn to describing the course of that struggle. First, it must be noted that the question of whether to besiege the fortress or only to blockade it was not definitively resolved from the very beginning; this is suggested, at the very least, by subsequent events. Nevertheless, based on all available official data, it can be assumed that the initial actions of the besieging forces—once they entered the fortress's zone of fire—were limited to a blockade. For this purpose, it seems that specific units from among the advancing armies were designated to form a so-called “blockade army.”

The situation preceding the establishment of the blockade line, as we saw above, developed in such a way that among the forces advancing from three directions toward Przemyśl, the units approaching from the east were the first to reach the appropriate distance for setting up the blockade line. These units, by September 7, had driven the enemy from the forward position at Medyka and occupied it. This circumstance led to the blockade line being strengthened first and most thoroughly on the eastern and southeastern fronts. As can be inferred from various correspondents’ reports, these sectors of the blockade proved to be the strongest during the subsequent phases of investment and siege.

Military theory states that the fortified siege line surrounding a fortress should be located 5 to 7 versts (approximately 5–7.5 km) from the fortress’s belt of forts. 1½ to 2 versts in front of that line, toward the fortress, advance outposts are to be placed, while 3 to 4 versts to the rear lies the main force.

In letters from correspondents who visited the fortress after the siege—having been to the headquarters of the besieging army, which, as is now known, was located near Mostyska, and having traveled across the entire surrounding area right up to the fortress’s core—there are references indicating that, on the eastern side, the main fortified positions of the siege line began near the village of Shekhinya, situated 4½ to 5 versts from the forts. This distance corresponds with the theoretical standard mentioned above. If we take it as the baseline and mark it to scale on a map in other directions (see Fig. 36), the main siege line would pass through the following key points: Shekhinya, Stroniavitse, Drozdovyche, Fredropol, Rokszyce, Olszany, Korytnyky, Kosenice, Troshchyce, Walawa, Buczów.

Judging by the fact that some of these points were mentioned at the time in various correspondents’ reports as being occupied by our forces during the blockade, it is reasonable to assume that the general direction of the blockade line, as shown in the diagram, is accurate.

The total length of this line comes to approximately 70 versts. The exact number of troops that initially occupied this line and how those troops were grouped is, for understandable reasons, nowhere specified. It is only known that the encirclement ring was divided into three fronts: eastern—which, evidently due to circumstances, assumed the greatest importance—northern, and southern; the latter two extended westward, forming a kind of secondary front, where, likely due to the situation, the blockade line was more weakly held than on the other fronts, at least during the September blockade.

Fig. 36. Diagram of the siege position.

By mid-September, Austrian field forces had been completely driven away from the fortress, which was cut off from the rest of the empire and left to fend for itself. Under these conditions, the garrison—on the eastern sector even pushed back from its forward positions—had no choice but to open artillery fire from the fortress against the besiegers’ works and then attempt to harass and dislodge them with sorties. However, as we learn from the official report of September 15: “the sorties of the Przemyśl garrison remain unsuccessful.”

According to unofficial sources (*), one such sortie ended with the complete destruction of three Austrian battalions, and our columns, pursuing the retreating enemy, captured one of the intermediate fortifications, seizing 300 head of livestock, a searchlight, and several machine guns.

*Telegram from Kyiv to Russkoye Slovo, dated September 29.

By the time mentioned above, as can now be judged from reports appearing in the press, the 11th Army, under the command of General Selivanov, had apparently been fully formed and was referred to as the “blockade army.”

In the second half of September, the Austrians, having somewhat recovered from the defeats we had inflicted and having reorganized their armies, jointly with the Germans launched new offensive operations. Our forces stationed at Przemyśl were evidently informed in advance about the enemy’s preparations for these new operations, and, as a result, it was likely decided to expedite the capture of the fortress and to transition from blockade to more decisive actions. This was likely facilitated by the entire situation developing around the fortress, which, after proper strengthening of the siege position, allowed our forces to come so close to the belt of forts that the high command—after an unsuccessful proposal to the garrison to surrender the fortress (*)—decided to storm some of the fortifications of the defensive belt during the period from September 23 to 25.

*This is confirmed by correspondences that appeared after the fortress’s surrender.

The official report of September 26 stated: The struggle with the Przemyśl garrison is unfolding favorably: our troops stormed and took one of the forward fortifications of the main position.”

Since permanent forward fortifications existed only in the southeastern sector, specifically in the Sedliska group, it can be assumed that one of the advanced forts from this strong group was taken by our assault.

Everyone in the deep rear of the war theater remembers how joyfully the official report mentioned above was passed from mouth to mouth, viewed by many as a harbinger of the fortress's imminent fall. However, as subsequent events showed, the fall of the fortress was still far off: storming permanent fortifications is not as easy a task as some imagine. It is often associated with significant losses and, if carried out without proper preparation, frequently fails to yield complete results.

As we learn from various unofficial sources that later appeared in print, the storming of the Przemyśl forts could hardly have been adequately prepared, due to the lack at that time of the necessary artillery and technical resources. For this reason, it cost us heavy losses.

Meanwhile, events to the west and south of the fortress were unfolding at full scale, for on September 23, Austro-German armies concentrated along the Toruń–Kraków front launched an offensive toward the Vistula and San Rivers. By September 27, their left flank had reached Sandomierz, and their right flank Sanok, with the main objective of relieving the fortress of Przemyśl, which we had surrounded.

These enemy operations compelled us to regroup our forces, as a significant portion of them had previously been drawn southwestward. Due to this regrouping, our troops were forced to retreat behind the line of the San River, and thus, starting September 28, the blockade of Przemyśl began to be lifted gradually from the western and southern sides, remaining only from the east, where the heavily fortified position described earlier (see Fig. 36) continued to be held by our troops.

Despite the large forces fielded by the Austrians, they were defeated everywhere—to the south of Przemyśl, on the lower San, and in the Carpathians. On October 24, our troops crossed the San River and finally drove back the Austrians. Thus, we once again secured the left bank of the river, which allowed us, starting October 29, to resume the temporarily interrupted blockade of the fortress.

For an entire month, the fortress had remained unblockaded on three sides and had the opportunity to restore communication with the rest of the empire and the army, serving as a point of support for the latter.

Although after the fall of the fortress the Austrian high command attempted to justify itself by claiming that it had been unable to fully supply the fortress during the specified period with military and food provisions, and to evacuate the wounded brought there after the August battles—allegedly due to bad weather that ruined the supply routes—nevertheless, from Austrian prisoners it was learned that the month-long break in the blockade had been used quite effectively by the enemy, particularly for bringing in new artillery and ammunition, and for strengthening the fort belt and the terrain in front of it.

Many temporary batteries and other constructions were built on the fort belt; new lines of artificial obstacles—wire entanglements, chevaux-de-frise, abatis, and especially land mines—were installed. Finally, many remaining wooded areas in front of the forts were cleared, and numerous trenches and artificial obstacles were created.

From a strategic standpoint, during the lifting of the blockade, the fortress played a significant role for the Austrians, serving as a strongpoint on the right flank of Archduke Friedrich’s advancing army.

Beginning on October 29, as mentioned above, the second blockade of the fortress began.

Competent military observers noted that, by this time, the situation on the Galician front did not necessitate hasty assault methods against the fortress; there was no operational urgency that demanded its fall at all costs and at the price of enormous sacrifices. Likewise, it was not deemed necessary to implement formal siege techniques, which are a further development of close investment and are sometimes entirely sufficient to compel a garrison to capitulate.

Subsequent events suggest that the high command under Przemyśl indeed adopted this perspective at the beginning of the new operations, since during the next three months, actions seemingly did not go beyond tight investment and relatively weak bombardment.

On November 5, the investment of the fortress began from the north and south, and by November 9, the ring of our troops had completely closed around all of Przemyśl.

On November 12, artillery skirmishes began, though at first, they seemingly did not reach significant intensity—especially from our side, presumably due to the continued lack of heavy siege artillery in our blockade army. The enemy, however, had already started at this time to bombard our blockade line with 24 cm and 30.5 cm mortar shells, though these inflicted no serious losses on our forces.

In the second half of November, the fortress garrison made several sorties, all of which failed. One such sortie was conducted with fairly significant forces under the command of the commander of the 23rd Division, Field Marshal Lieutenant Tamási, but it also achieved no success and ended only with our forces capturing several hundred Austrian soldiers.

Communication between the fortress and the rest of the country was maintained exclusively through aircraft and radio telegraphy. During November, the information delivered bore the most favorable character for the Austrians: it was reported that the Russian army had allegedly been defeated, that the Austrian troops were advancing victoriously in the Carpathians, and that the liberation of the fortress was near. Naturally, this maintained a cheerful spirit within the garrison, and, according to prisoners, a festive mood prevailed in the fortress during this period: café-concerts flourished, concerts were held, and there were jokesters writing poems on the theme of the Russians’ inability to capture the fortress.(*) Posters with such verses were hung on forward positions and dropped as leaflets to our troops from airplanes. But at the same time, according to deserters, the garrison suffered from the onset of frost, reaching -15 to -16°C (5°F). Every morning, long lines of lower-ranking soldiers with frostbitten limbs were delivered to the hospitals.

*See: "Letters from the War" in Vechernye Vremya, December 8.

As for the condition of the blockade army during this period, some reports indicated that overall, the army’s operations were quite successful and that it was in the best possible conditions for an active military force: food supplies were uninterrupted, every large unit had its own bathhouse; resting troops were quartered in the homes of nearby villages close to the blockade line, while those on the forward positions lived in dugouts with wooden floors covered with straw. The army’s morale remained very high until the last days of November.

Regarding the blockade position itself, it was being continuously improved: solid dugouts and observation posts were built in the trenches, and a variety of artificial obstacles were placed in front of them. On the siege batteries, which were located much further to the rear, solid dugouts and storage niches were also arranged.

At the same time, the troops holding the blockade line used every opportunity to advance into the forward terrain, securing individual sectors of it and tightening the siege ring ever more closely.

In the last days of November, the Austrians made their first attempts to relieve Przemyśl. For this, our opponents developed a plan according to which the Germans were to advance in Poland, and the Austrians from Kraków and across the Carpathians. The Germans, by advancing in Poland to occupy a defensive line along the Vistula River, were to draw as many of our troops as possible to that front, thereby thinning our forces on the Austrian front. This, in turn, was to make it easier for the Austrians to break through our lines in the Carpathians and relieve Przemyśl.

These operations created a rather serious situation for our blockade army, which, as one of our military observers indicated, even resulted in a brief and partial lifting of the blockade, apparently from the southern direction.

The fortress garrison, having received information from aircraft about the Austro-German offensive, apparently decided to coordinate its own active operations with it. According to our official report from December 4, between November 27 and December 3 (over the course of a week), the garrison attempted several sorties, but all of these were repelled by us with heavy losses to the garrison.

On December 2, the garrison launched two simultaneous sorties—one to the north, the other to the south. It seems that the southern sortie was intended, in the event of success, to establish contact with the approaching Austrian army, while the northern sortie may have been conducted to divert our attention from the breakthrough point or to destroy our siege works.

Both sorties were repelled. In the course of these battles, we captured over 300 prisoners and three machine guns.

On December 4, the Austrian army approached the Sanok–Lisko front, on the upper course of the San River, 45 versts (about 48 km) from Przemyśl. But our troops immediately went on the offensive and, in a two-day battle, defeated the Austrians.

To support their field forces, the garrison of Przemyśl launched another sortie on December 4, this time with significant forces. The Austrians attempted to break out of the fortress in a southwestern direction, toward Bircha, located 12 versts (approx. 13 km) from the fortress forts and 25 versts (approx. 27 km) from Sanok. The battle continued December 5 with great intensity and ended only on the night of December 6.

According to our official report, our troops fought under favorable conditions: the Austrians, attacked on the flank, were repelled and lost many prisoners. According to unofficial sources, our troops breached wire entanglements at one location and captured one of the fort belt's fortifications, taking half a company, including an officer, prisoner and seizing one machine gun. In the village of Visotsko, our forces captured an airplane with an officer pilot and a supply of leaflets.

Nevertheless, despite this latest failed attempt to break through and link up with the Carpathian army, the fortress garrison on December 7 and 8 again made sorties, though this time with smaller forces and in various directions.

All sorties were repelled. Several enemy companies that advanced too far forward were completely wiped out. In the process, we captured 1½ versts of field railway, 2 officers, 100 enlisted men, and 2 machine guns. The machine guns taken from the enemy were immediately used to fire on approaching reserves, inflicting heavy losses. Among the belts taken from Austrian machine guns were belts loaded with explosive bullets.

The garrison continued such unsuccessful sorties on December 9 and 10.

The failed breakout attempt by the defenders of Przemyśl to the south, aiming to meet up with the field army, and the success achieved by our troops in December in the Osławy River valley, in the Sanok and Lisko areas, finally shattered the garrison’s hopes for the fortress’s rescue, and morale dropped sharply.

Although during the following days of December the garrison remained active through sorties and reconnaissance, their efforts were already significantly weakened. From this point, according to prisoners, it became known within the garrison that there was a shortage of food. Requisitions from private individuals began, rations were reduced, and horse meat was issued. Troops were reluctant to go on sorties, believing they were being sent to slaughter.

The final sortie of December took place on December 15. It too was repelled. Our troops captured several tactically important heights and took 2 officers, 184 enlisted men, and one machine gun.

In total, according to official reports, during the repulsion of the November and December sorties, we captured 27 officers, 1,906 enlisted men, 7 machine guns, 1,500,000 cartridges, 1½ versts of field railway, and large quantities of weapons and equipment.

Our own losses, according to the same report, did not exceed 60 enlisted men and 4 machine guns, and these losses were mainly sustained during an engagement in which two Austrian regimental units managed to overwhelm one of our forward companies, which could not be reinforced in time.

According to participants in the siege of Przemyśl during November and December, the fortress garrison frequently conducted reconnaissance using airplanes, which from early morning flew over our blockade lines and signaled the positions of our trenches. When the trenches lay outside the range of fire from the forts, the aviators would bomb them.

The fight against enemy aircraft, according to the same sources, was fairly successful, and by the end of November and beginning of December, our forces managed to shoot down two aircraft. It was established that, in addition to reconnaissance, the garrison used the aircraft to deliver supplies, as one downed aircraft was found to be carrying about 10 puds (approx. 160 kg) of various canned foods.

To correct their artillery fire, the garrison also used tethered observation balloons.

According to private reports, during the second half of November and in December, Russian aviators also made flights over the fortress and dropped bombs, which reportedly had a demoralizing effect on both the civilian population and the garrison.

There were also more serious results reported from our aviators’ actions: in one case, an ammunition depot was blown up; in another, an entire supply convoy carrying food and military equipment to one of the forts was smashed to pieces. Finally, aviators also surveyed the effectiveness of our siege artillery.

Among other technical means, the fortress garrison, according to some reports, made use during the indicated period of carrier pigeon post and searchlights; the latter were apparently quite numerous in the fortress and caused significant disturbance at night to our sentries and reconnaissance units. On our side, searchlights were also employed.

During the December sorties, some of our enlisted men involved in repelling the attacks suffered severe facial burns and eye injuries. After a thorough investigation and interrogation of prisoners, it was established that the Austrians had used devices delivered from Germany for spraying concentrated sulfuric acid; these devices operated for about a minute and were effective in a distance of 30 paces.

From mid-December to Christmas (New Style), according to prisoners’ accounts, the garrison’s morale was depressed, resulting in a lull in activity: sorties ceased, and fortress artillery fire became relatively slack.

According to eyewitnesses, on Christmas Eve (New Style), fortress artillery fired only until noon, after which the Austrians—apparently preparing for the Holy Night—ceased fire. Our troops also stopped firing. On the first day of the holiday, the day was entirely quiet. Only in the evening was some movement noticed within the fortress: it turned out that, taking advantage of the holiday confusion in the city, several Austrian soldiers—Rusyns—ran over to our side and surrendered; after them came a volunteer of ours who had escaped from Austrian captivity.

In one issue of the Vienna newspaper Neue Freie Presse, published after the fall of the fortress, several episodes of life in the besieged fortress are recounted, including how the garrison spent the Christmas holidays. On Christmas Eve (New Style), the garrison of Przemyśl, according to the paper, received holiday greetings from the besiegers. The Russians did not fire on that day or the next, allowing a charity concert, religious procession, and ceremonial military parade to take place in Przemyśl. The fortress defenders were very moved by such chivalrous behavior by the besiegers and, in return, completely ceased military activity on Russian Christmas.

On New Year's Day (New Style), the same newspaper claims that unofficial envoys from the besiegers appeared at the fortress and delivered a message of thanks for the correct and respectful conduct of the Austrians during the holidays.

The first half of January passed with the same calm as the end of December. In the fortress, according to those besieged, the most popular people were the aviators, whose arrivals from the outside with the latest news caused tremendous excitement. Our aviators continued to fly over the fortress, dropping bombs and taking photographs of the city and its surroundings.

Our troops surrounding the fortress continued to advance gradually, especially from the south and southeast, capturing prisoners during their movement and securing the seized areas. This advance and consolidation, as can be judged from later published letters from siege participants, was accomplished by means of trench and sapping operations.

Thus, it may be assumed that by the beginning of February, the high command, feeling confident beneath the fortress, decided to transition from close investment to more active operations, though not risking a direct assault on the forts, recalling the failed storming attempt of September.

In the first half of February, the garrison of Przemyśl undertook no sorties, but fortress artillery was highly active, daily firing a considerable number of heavy shells at the positions held by our troops. However, this fire proved completely ineffective: for every 1,000 heavy bombs fired by the fortress, there was often only one wounded on our side.

The Austrians were particularly aggressive in firing at our airplanes, which flew almost daily over the fortress. Numerous shrapnel shells burst in the air, but this firework display was always completely ineffective.

As revealed by one of the Austrian generals (a Slav by origin*) after the fortress’s surrender, at the very beginning of February, aviators brought news to the fortress of intense battles near Koziuvka and in other areas of the Carpathians, involving significant German forces. Fortress commanders began spreading rumors among the garrison that these operations were intended to be combined with a major sortie from the fortress, which would break the blockade and strike at the rear of the Russian army in the Carpathians once it reached a certain point. Then, they claimed, Przemyśl would be permanently freed.

*See: Vechernye Vremya, April 7, 1915

From that moment, morale in the fortress rose again and with each day, buoyed by new reports of German attacks in the Carpathians, it continued to climb rapidly.

But just as quickly, morale began to fall again, giving way to despair, as week after week passed and the air mail no longer brought any comforting news, except for reports that the attacks in the Carpathians—both Austrian and German—were continuing without any decisive success. It was around this time that more tangible signs of famine began to appear in the fortress. However, as some claim, the hunger was felt only by the Slavs, for only they had their rations reduced, while Germans and Magyars were secretly issued increased portions. Slavic prisoners who fell into the hands of our troops were visibly emaciated and themselves explained it as due to undernourishment.

Discord began to spread among the multiethnic garrison; absurd rumors circulated, dissatisfaction with the command grew, and the hopelessness of the situation became obvious to everyone. Written and printed orders to hold out “at all costs” no longer had any serious effect on the lower ranks. Slavic soldiers returning from the forward trenches—where they were mostly sent—spoke of the tightening siege ring and the impossibility of fighting the Russians, who were well-fed and warmly clothed. Often, according to participants in the defense of the fortress, only half of the men sent to the trenches would return, while the rest, unable to bear it, surrendered in groups and were shot in the back by their own comrades.

This described situation emerged in the second half of February, when, according to the former besieged, our troops transitioned to a proper siege, i.e., intensified advancement via sapping and trenching, bombardment with higher-caliber artillery, and the gradual capture of the enemy’s forward trenches.

On the night of February 28, our troops, in a sudden assault, drove the enemy from a heavily held forward position on the northern front of the fortress, near the villages of Malkovitse–Valava, 1½–2 versts from the fort belt. During this action, our troops captured 8 officers and 400 enlisted men, 2 machine guns, 2 telegraph sets, many wires, and rails from the portable field railway.